Friends, can you smell that positively divine aroma of fresh ginger, turmeric, cumin, chilies, and mustard emanating from your computer screen?

Thanks to First Daughter Sameera “Sparrow” Righton and her creator, Mitali Perkins, we can enjoy some authentic Indian food at our Asian Pacific American Heritage Month potluck today!

I don’t know about you, but I’m ready to don my salwar kameez and bhangra around the kitchen. I just read the first two books in Mitali’s First Daughter series, First Daughter: Extreme American Makeover, and First Daughter: White House Rules (Dutton, 2007, 2008). Loved them.

I admit I didn’t know quite what to expect. I had enjoyed The Not-So-Star-Spangled Life of Sunita Sen and Monsoon Summer. Positively adored Rickshaw Girl, which, as you probably know, has received loads of well deserved accolades, the latest of which is the 2008 Jane Addams Honor Award.

In 16-year-old Sparrow, I found a highly intelligent, compassionate, resourceful humanitarian, who just happens to be the President’s adopted daughter. In Extreme American Makeover, we see how Sparrow’s strong sense of self prevails, despite a physical makeover and attempts to “Americanize” the Pakistani heritage out of her while her dad is running for office.

Once her dad wins the election, they move into the White House, where things get even more interesting. In the second book, we see just how many of the White House “rules” Sparrow adheres to, as she interacts with her cousin Miranda, plays Cupid for her mom’s personal assistant, hangs with her SARSA friends at the Revolutionary Cafe, longs for her soulmate, Bobby, deepens her friendship with not-so-privileged Mariam, and of course, continues to blog. Despite the restrictions of a high profile lifestyle, somehow Sparrow manages to stay true to herself and positively affect those around her.

And how about those oatmeal scotchies! We first tasted them in Extreme American Makeover, but in White House Rules, these frosted wonders take on a life of their own. After the Swedish Ambassador raves about them, they become a staple at White House teas, enabling Miranda to earn some needed funds. Never underestimate the value of farm fresh milk! All I know is, I MUST make those cookies. Good thing Mitali has linked to some scotchies recipes here.

Speaking of recipes, Mitali has brought a childhood favorite today. She says, “We used to eat this almost every day when I was growing up. I LOVED it as a kid, mixed with steaming basmati rice and a side of hot mango pickle, and still do!”

So go ahead, whip this up. You know you want to. And while it’s simmering, peek into the White House to see what Sparrow is up to. I want her there come November.

BENGAL RED LENTILS (MASOOR DAL)

1-1/2 cups red lentils

3-1/2 cups water

6 sliced serrano chilies

1/4 tsp turmeric

1-1/2 tsp salt

4 T vegetable oil

1 cup minced onions

1 cup chopped tomatoes

1 T grated fresh ginger

1 T panch phanon mix (equal proportions of whole cumin, fenugreek, anise, mustard, and Indian black onion seeds mixed and sold as one spice; you’ll need to get this at an Indian store and it’s called “five spice mix”)

4 dried small red chilies (depending on how spicy you want it)

3 cloves crushed garlic

1. Rinse lentils well, add water, serrano chilies, turmeric and salt. Bring carefully to boil and cook over low to medium heat, partially covered, for 25 minutes. Cover and cook another 10 minutes. Adjust salt.

2. While lentils are cooking, cook onions in a frying pan in two tablespoons of oil until they are golden brown (approximately 10 minutes), stirring constantly. Add tomatoes and ginger and continue cooking until the tomatoes turn into a delicious and fragrant mush (approximately 8 minutes). Stir constantly so that tomato mixture doesn’t stick. Turn heat to low if necessary.

3. Scrape out the tomato mixture into the lentils and stir it in. Let lentils sit while you make the spiced oil.

4. Do a quick rinse of the frying pan, without soap, and dry thoroughly. Add the remaining two tablespoons of oil and heat over medium high heat. When oil is hot add panch phanon mix and heat until the seeds begin to pop, about 15 seconds. Add red chilies and fry for another 15 seconds, until they turn a little darker. Turn off heat and add the crushed garlic and let sizzle for about 30 seconds. Stir this mixture into the lentil/tomato mixture and serve with rice. Adjust salt.

*

First, test your general sushi knowledge with

First, test your general sushi knowledge with  To find out what type of sushi you are,

To find out what type of sushi you are,  If you’re a sucker for games, try

If you’re a sucker for games, try  An excellent primer featuring a little history and how to make sushi from Good Eats’ Alton Brown:

An excellent primer featuring a little history and how to make sushi from Good Eats’ Alton Brown:  Just for fun:

Just for fun:

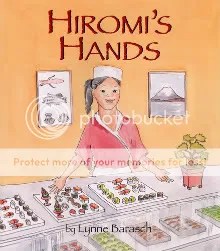

And finally, For the Kids, the best sushi picture book ever (review coming next week):

And finally, For the Kids, the best sushi picture book ever (review coming next week):

Black sand beach, Island of Hawai’i

Black sand beach, Island of Hawai’i